The Traps of Accommodating Resistance

Accommodating resistance is a staple in the training of many a conjugated equipped lifter. While it has its uses- it has its drawbacks, too. Something I realized when helping good friend Jake Plattner troubleshoot his squat was that people don't really talk about said drawbacks much, and that leads many to making the same mistakes.

The prime culprit for a lot of these follies is bands- in particular large amounts of them equating to a high percent of the lifter's squat- but more on that later. Before we get to that, we need to address an even bigger elephant in the room: time.

Most of us learned about accommodating resistance through Westside. This is great, but a lot of us were missing something that many lifters talked about in Book of Methods have: decades of time lifting against straight weight exclusively. For them, bands were a novel stimulus. They were truly accustomed to the straight bar and straight weight. However, lifters like myself (and my friend Jake from above) have yet to have that time under the bar. For reference, I am 21 and so is Jake (at time of writing of course). Some lifters at Westside had the equivalent of our entire lifetimes lifting without accommodating resistance before it was discovered and honed. We came into the sport with bands, chains, and specialty bars all at our disposal immediately- this leads to some of us spending more time with variations than we ever had with a straight bar and straight weight, which sort of nullifies some of the underlying purposes of them.

To drive this point home further, bands and chains were brought into Westside Barbell in the 90s. Although his OpenPowerlifting only goes back to 1979, Louie actually did his first meet in 1966 (you know, the one where he placed 10th out of 11 lifters, only beating some old guy and decided he was done with Olympic lifting forever). Even going from 1979 to 1990, that's a minimum of 11 years of hard competitive training before touching a band or chain. In reality, it was at LEAST 24 years of powerlifting training (not counting his Olympic lifting background) before Louie was exposed to accommodating resistance.

I'm not saying new lifters should not touch bands or chains for decades. That is silly, we have since learned a lot and should be receptive to new ideas. They can still make you better. What I am saying is to take everything you hear from lifters with such experience with a grain of salt. While Louie's works are absolutely groundbreaking, remember everyone in that gym was of at least Top 10 potential, if not record breaking potential. A lot of lifters aren't there yet, and it can be hard to translate such concepts down to those levels.

The other half of this is some lifters never even consider the strength curve and how it applies to them. Accommodating resistance is effective because it meets the lifter's strength curve, and this is almost always good for dynamic effort work as it can force the lifter to learn to push through the entire rep and not get lazy at the top. However, on max effort days and in accessory work, we need to take an honest assessment of where we are weak. If we are weak at the bottom of any lift, accommodating resistance will only exacerbate this issue. Not only does it not assess where you are weak, it furthers the imbalance by making the top end of the lift stronger!

A mental aspect of accommodating resistance that makes it even more alluring is top end calculations. While vaguely indicative of the direction of training if tracked properly, they are rarely directly relevant to a lift. I have known lifters to take over 1000lbs at the top of a circa max peak just to go squat less than 800 at the meet. Admittedly, when I experimented with a circa max phase myself; I ended up taking the equivalent of a 740lb double to a box with the straps down- only to bomb with my opener of 665lbs! I cannot speak for every system, but if you are training under the conjugate umbrella I would encourage you not to bother with such calculations. Instead, track accommodating resistance setups like variations, and break PRs against them. For example, I have a PR in full gear against blue bands. It may be fun to think of what that is at the top, but all that really matters is the next time I cycle back to it I add more straight weight to that same setup.

There are also some aspects exclusive to bands that need to be touched on. Too much band tension can do a few things: ground you (forcing your feet into the floor as opposed to you actively rooting them), track you (the bands have their own groove, which can turn the bar into a smith machine when there's too many of them), and change velocities (the bands pull you down faster than gravity, which can alter your eccentric phase if you grow accustomed to it). If used too much, these can wreak havoc on your lifts when you touch straight weight again. While chains do not have these problems, they can succumb to the strength curve issues discussed above.

All of this considered- a problem presented without a solution is simply a complaint. So what is a lifter to do if they have fallen into the trap of overzealous amounts of accommodating resistance too early?

You need to adjust your frequency and length of use. This can be done in a few ways. My favorite is creating synergistic sessions/days. For instance, if I use a lot of accommodating resistance on my DE days for a wave, I will gravitate more to straight weight on my ME days (or vice versa). You can also alternate weeks of heavy accommodating resistance with weeks of straight weight. Part of the beauty of the conjugate system is how malleable it is, but people take that the wrong way. If you struggle with straight weight, you can just use it more often. It can quite literally be subbed in anywhere. Remember, there was conjugate before accommodating resistance even existed!

To address weaknesses possibly developed in the bottom of a lift, I will not insult your intelligence by telling you what muscles to train. There are many resources already written about this. You can seek them out and shift accessory work appropriately, just know your individual muscular weaknesses leading to those movement deficiencies may be unique to you and your leverages (another reason I don't want to write about that particular aspect- it is difficult to prescribe with no context). However, another surefire way to get better at the bottom is to spend more time there! Reps and pauses can help.

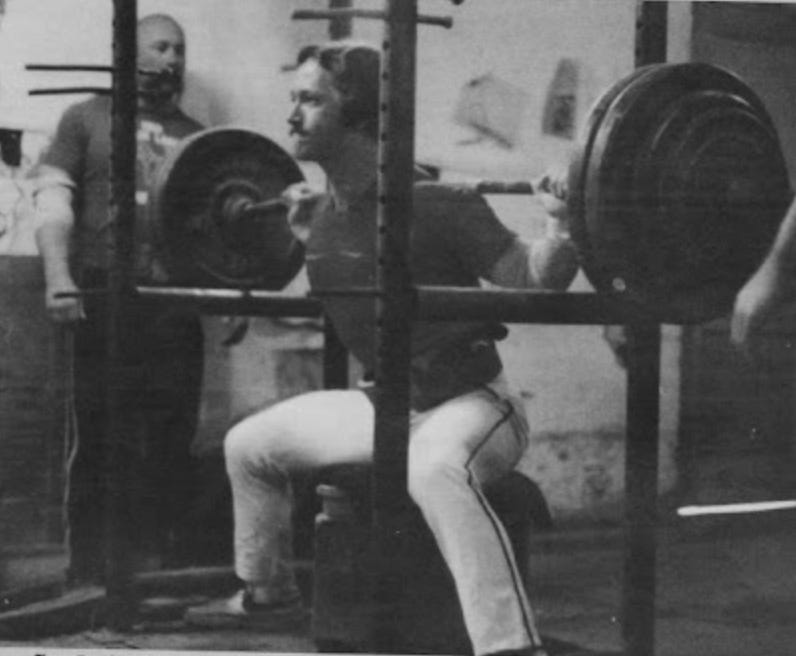

I write this not to bash accommodating resistance; I love it and use it all the time. Just look at any of my training footage! But I have been stung by it before- and want lifters to understand why they may not be getting as much out of it as they have read about. Hopefully this will either save you the headache or help you recover a lift fallen victim. They are a tool in training, no more and no less.